You enter the Huddersfield Narrow by going, Harry Potter-like, though a concrete wall. That is, you go under a road which had been widened while the canal was closed, leaving only a pipe for the water. The reinstatement of a bridge here by the then County Council was one of many such blockage removals which enabled the canal to be reopened.

Straight away you pass an old warehouse and reach the first

of the 42 locks which will take you up to the moors. You are

going through the University here. Pass straight through the

head of the next lock chamber and into a new cutting which gets

you under a factory, through two new locks, and emerge beside

another college which takes full advantage of its city centre

canalside. Stop if you need it at the nation's biggest chandlery

chain (B&Q) then go under a rather elemental lattice railway

viaduct and into an unfrequented back part of the town. You

emerge in Milnsbridge, with a succession of determined mill

conversions and new buildings. Moor at the wide and explore

quite a useful compact high street. The locks are close together

as you climb rapidly up the Colne Valley to Golcar, which has an

attractive tight-bended aqueduct taking the canal onto the other

side of the river. There's a small museum of weaving life here.

Across the widening valley bottom is Titanic Mill,

everything its name implies and converted into super-posh flats

- sorry, apartments. You go on through pretty woodland, and past

not-yet-restored mills. Don't neglect the steep walk across

fields to the Olive Branch. In a while you get to Slaithwaite,

which gave the restorers a real headache because the canal had

been comprehensively eliminated. The measure of their success is

how well the canal seems to fit into the town.

Slaithwaite

make a good overnight mooring. More woods and enticing views of

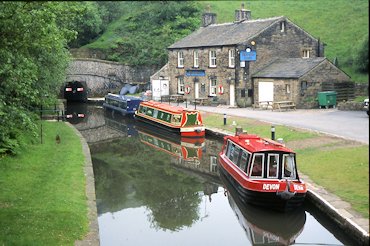

the hills bring you to the bottom of the Marsden flight. These

last twelve locks take you quickly up above the town to the

summit. You need to moor here till it's time for your tunnel

passage, so walk down into the town and find useful shops and a

good choice of pubs plus one by the canal at the railway

station, and the Tunnel End. Visit also the Visitor Centre, with

excellent material and audio-visuals on the canal, building the

tunnel, packhorses before the canal, and centuries of social

history.

Now comes the highlight of your journey.

Accompanied by a knowledgeable person from Canal & River Trust,

plunge into the inky depths below Marsden Moor. Soon the tunnel

bore opens out into naked rock, and your guide will show you the

marks where the navvies bored hole by muscle power ready for

blasting of the rock. After a couple of hours you emerge in

Lancashire. The Diggle Hotel beckons, then you sweep down the

flight, with extensive views, before passing under an amazing

viaduct and over Old Sag, a little aqueduct, and arriving in

Uppermill. This is worth a decent stop, with shops, pubs and in

interesting museum of local life.

The canal now drops away

through a mixture of greenery, new development and sites whose

owners haven't yet seen the light; always changing and always

interesting. Greenfield makes a good stop. Rather suddenly you

arrive in Stalybridge, a town not without its problems but also

with real charm. There's a Tesco right by the canal, and streets

of shops nearby, criss-crossing the canal, large parts of which

have been rebuilt from scratch.

Below Stalybridge there is a

short rather grotty stretch which perks up below the bottom lock

at the invisible junction with the Ashton Canal, and leads

through a tunnel under an ASDA to Portland Basin, which has a

fascinating and extensive museum in a reconstructed warehouse

and a candidate for the most graceful footbridge anywhere on the

canals. The Huddersfield Narrow packs 74 locks into 20 miles and

reaches the highest point on any English waterway, with the

longest tunnel. It makes an unforgettable journey.

Boating on the Huddersfield canals

The Huddersfield Broad is like the Calder & Hebble without the handspikes. Don't lift the gate paddles too soon as you go up, and keep away from the cill as you go down. There is neat lift bridge which you work with a CRT key, and can have fun with in rush hour.

The Huddersfield Narrow is freely available from either end up to points some way below each side of the summit - Lock 32W and Uppermill. Between these points traffic is controlled to limit demands on water and staff time. Passage over the summit and through Standedge Tunnel is available on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and must be booked (0303 0404040). Limited passage may also be available to boats wishing to moor at Marsden without going through the tunnel. Water supply is restricted, and boats are asked to keep at least two locks between them, to give time for recovery.

Click to see CRT info for the Huddersfield Narrow Canal and Standedge Tunnel

The Huddersfield Canal - a little history

If

a large part of the attraction of the Huddersfield Narrow to

leisure boaters is its sheer improbability, its ill-chosen route

meant it was the most challenged of the three trans-Pennine

canals (or four if one counts the High Peak Tramway linking the

Cromford Canal with the Peak Forest).

The route was chosen

not as the best route across the Pennines, but because the

Ashton Canal wanted access to Yorkshire. It became inevitable to

cross Marsden Moor, but in order to obtain water in crossing the

watershed it was necessary to go across at a lower level, hence

the tunnel. The canal itself was built quickly enough, completed

by 1799, only four years after the Act. The tunnel took another

twelve years, eating money and lives.

To get the Act against

opposition from mill owners, the company had to agree to take no

water from the rivers beside which the canal was built. Thus it

was fed entirely from reservoirs.

So the canal opened fully

in 1811. It faced difficulties over the change of gauge at

Huddersfield, and short narrow boats were built to avoid

transhipment but of course could carry less. Competition from

other canals affected revenue. Then by the early 1840s the

railways made their move, and as early as 1845 the canal had

sold out. Traffic on the canal held up well for most of the

century, but became concentrated at the ends; traffic through

Standedge had finished by as early as 1905. By the end of the

First World War there was little moving, and the Huddersfield

narrow fell victim to the notorious LMS abandonment in 1944.

So the HNC was one of the canals which was nationalised in 1948

because it was part of a railway. It was maintained as a water

channel, and the locks were gradually filled in and the bridges

dropped. It was in a pitiful state when in 1974 the people who

had achieved the reopening of the Ashton and lower Peak Forest

looked around for something to do.

A stunning campaign was

run by the Huddersfield Canal Society. Hearts and minds were

converted, and the money started to follow. British Waterways

gradually played a more active part, going way beyond what they

were supposed to do - maintain the canal strictly at lowest cost

as a water channel. Since the canal reopened in 2001, further

huge steps have been made in improving the locks and reducing

leaks. There are still challenges ahead, not least the legacy of

that early concession, not to use river water. But the canal has

definitely come back to robust life; a miracle.

Further reading

Pennine Dreams - The Story of

the Huddersfield Narrow Canal by Keith Gibson

The

Huddersfield Narrow Canal: Two Hundred Years in the Life of a

Pennine Waterway by Keith Gibson and David Finnis